Effective IAM for AWS

Why AWS IAM is so hard to use

Why AWS IAM is so hard to use

The AWS Identity and Access Management system is a feat of modern engineering, correctly and quickly enforcing access controls at massive scale. The access evaluation engine is ubiquitously integrated, highly available, and quickly processes hundreds of millions of access requests per second. Engineers can use the flexible and powerful policy language to authorize access to all infrastructure and even applications.

But interviews with many Cloud, DevOps, and Security engineers revealed problems with AWS IAM.

Engineers say it's hard to:

- Write policies that do what they intend

- Understand what all the policies actually do

- Validate access controls without breaking things

Even experts find it difficult to create policies that do what they intend. My research found most practitioners feel like understanding who has access to their data is impossible.

The usability of AWS' powerful security policy engine leaves much to be desired. The problem is not that AWS IAM doesn't have enough features. The opposite is closer to the truth. There are many features, features interact in ways that are difficult to understand, and feedback on the correctness of a policy is slow and inadequate.

This chapter explains why AWS security policy engineering is so hard, and offers solutions to those usability problems. The 50+ engineers I interviewed really want to create good policies. They fear letting down customers when they don't. However, because policy development and testing is difficult, engineers run out of time, energy, and patience to do it well without blocking delivery.

We'll examine the design of AWS IAM and uncover problems that make it difficult for engineers and teams to use it correctly.

First, you'll learn IAM's complicated process for evaluating security policies to determine whether an API action should be allowed or denied.

Second, you'll learn how the flexibility of the AWS security policy language makes it difficult to identify what is in scope and how policies interact.

Then we'll examine IAM's usability through the lens of design to identify the problems that make it difficult for engineers and teams to use correctly.

Finally, we'll discuss how to address these design problems with components that wrap IAM's power in a usable package.

How AWS Security policies are evaluated

Let's uncover why evaluating the effects of AWS security policies is hard.

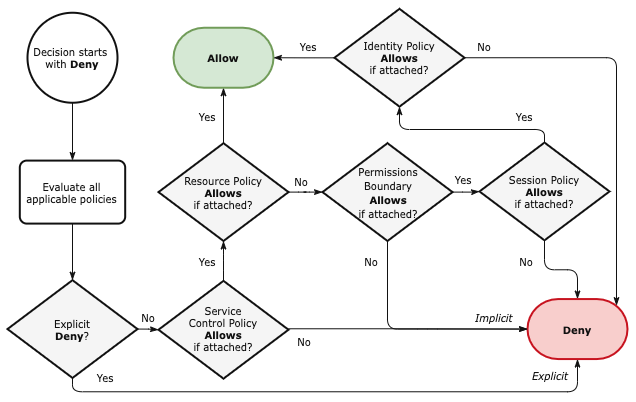

This flowchart depicts AWS IAM's security policy evaluation logic:

Figure 2.1 AWS Security Policy Evaluation Logic

Each of the five types of security policy are integrated into the access decision making process. This is not simple to understand or evaluate.

Did you notice there are two paths for allowing access when a service supports resource policies? Look for paths to the green end state.

AWS IAM evaluates all the policies in scope for the account, principal, session, and resource. Any of those policies might Deny or limit access. Two kinds of policy may Allow access, Identity and Resource.

An Identity policy attached to an IAM principal can grant access to a specific resource or many resources, e.g. an S3 Bucket or all DynamoDB tables.

When an AWS service supports resource policies, a Resource policy can also grant access to the resource it is attached to, e.g. an S3 bucket or KMS key. More than 20 AWS services support resource policies, primarily those where it is useful to share a resource across accounts.

Resource policies are very powerful and have their own quirks. For example:

- Resource policies can grant permissions past a Permissions Boundary or Session policy in several scenarios, particularly when allowing an STS session directly or to an IAM role via Condition.

- KMS key policies are the primary way to control access to encryption keys and introduce an exception to the standard policy evaluation flow. The account's Identity policies are only integrated into the policy evaluation flow when access is granted to the account's root user. 😲 This makes implementing least privilege easier, but diverges from the standard model of allowing access from either Identity or Resource policies.

To understand effective access, engineers must evaluate these policies too.

Merely gathering a principal’s in-scope Identity policies is complicated.

Engineers need to account for all Identity policies managing an IAM principal's access. This might include:

- AWS Managed Policy attached directly to the IAM role, user, or a group the user belongs to

- Customer Managed Policy attached directly to the IAM role, user, or a group the user belongs to

- Inline policy attached directly to the IAM role, user, or a group the user belongs to

IAM supports attaching up to 10 policies to a role or group by default; AWS support can raise that limit to 20. An IAM user can be a member of up to 10 IAM groups. See IAM Limits for full details.

Depending on where you define policies, engineers may have to account for many policies, defined in many places.

And while convenient to grant a lot of access quickly, AWS Managed Policies:

- Do not limit resource scope. Actions in the policy apply to all resources in the account. So when the

ReadOnlyAccesspolicy is applied to an IAM principal, it covers all resources and data in the account. Every S3 bucket, DynamoDB table, EBS volume, etc. - Change over time. For example, the

ReadOnlyAccesspolicy updates to grant read access to new services soon after launch. Even service and job-specific policies see updates. (💡 follow the MAMIP twitter account by Victor Grenu for updates)

⚠️ This policy evaluation logic also doesn’t account for service-specific access control systems such as S3’s Object ACLs, which are an extra layer applied in addition to IAM. Of course it is still the engineer’s responsibility to understand how these work together.

Identify what's in scope

A security policy can bring a lot or a little into scope.

Control access to any resource described the form and operation of AWS security policy and statement elements. The Principal, Action, and Resource elements may include a very narrow or very wide scope, particularly when using wildcards.

Here are some examples :

| Element | Narrow | Medium | Wide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | Fully-qualified IAM role ARN:arn:aws:iam::111: ↲ role/app | N/A | Another AWS Account: 123456789012 or All AWS accounts * |

| Action | Specific actions:["s3:GetObject","s3:GetObjectAcl", "s3:PutObject"] | All S3 actions starting with GetObject:"s3:GetObject*" | Full access to S3:s3:*or full access to AWS APIs: *:* |

| Resource | Specific bucket and object:["arn:aws:s3:::app-data", "arn:aws:s3:::app-data/file-1"] | All objects in a dedicated bucket:["arn:aws:s3:::app-data/*"] | All objects in a shared bucket: ["arn:aws:s3:::shared-data/*"or all Buckets: *(this is what AWS Managed Policies do) |

Condition - aws:PrincipalArn | arn:aws:iam::111: ↲ role/app(Same as Principal) | All IAM 'app' roles with a known variation:arn:aws:iam::111:role/app-*or arn:aws:iam::111:role/env-prod/app-???????? | Another AWS Account: 123456789012 or All AWS accounts *(Same as Principal) |

Table 2.1 How wildcards affect scope

So engineers now have a huge information gathering and evaluation task to perform. They must correctly:

- Retrieve from zero to tens of identity policies that may be directly attached as a managed or inline policy, or indirectly attached via a group, again managed or inline.

- Retrieve resource policies for relevant resources involved in the request path, e.g. S3 bucket or KMS key.

- Parse the policies and build a mental model of what each statement brings in and out of scope.

- Calculate the effects of the statement, properly accounting for

Effectprecedence and negation.

But engineers usually do this in their heads with less than perfect information about the policies in their system and how IAM works.

Mistakes will happen.

Engineers will get the Allow path to work. No team is going to give up until the application or person's principal's can execute requests successfully. But most teams will move on long before achieving the least privilege they intended.

Figure 2.2 Implementing Least Privilege to Resources

Because for engineers to grant only the access they intended to principals and resources, two non-obvious things should be included in their security policies:

- Identity policies attached to principals should scope resource access to implement least privilege for the principal

- Resource policies should allow intended principals and deny everyone else to implement least privilege for the resource

Don't let anyone minimize this task.

Writing minimal access policies is impossible for humans working with real systems without serious help.

Problems with the usability of AWS IAM

The biggest problem with AWS security is that most people cannot confidently configure security policies using information they have in their head or at hand. They need to look things up constantly, and they're still unsure. While configuring security controls is an 'everyday' experience, engineers cannot configure policies quickly and correctly enough to achieve their goals.

This is not the engineers' fault.

Engineers are using a system which has not been designed for usability.

The AWS security policy system requires users to know and understand a tremendous amount in order to use it effectively. Engineers must understand a lot about how AWS security policies are evaluated, how the policy language works, the features of the policy language for a given service, and the state of the system in order to create a mental model and finally create policies.

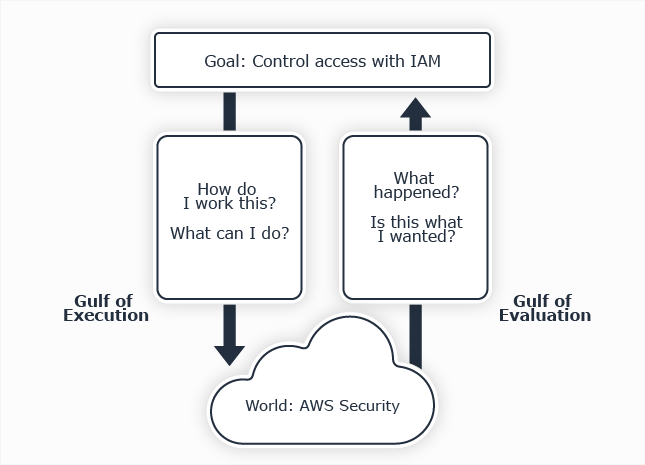

This is a serious usability problem because there is a large difference between what most engineers have and what they need to secure resources effectively. Engineers must expend a lot of effort to configure AWS IAM correctly. Usability expert Don Norman describes this as two "Gulfs"1 in The Design of Everyday Things:

Figure 2.3 The Gulfs of Execution and Evaluation for AWS Security

To complete their goal of controlling access with IAM, Engineers must cross two gulfs:

- The Gulf of Execution, where they try to figure out how to use IAM

- The Gulf of Evaluation, where they try to figure out what state IAM is in and whether their actions got them to their goal

Engineers have difficulty answering Norman's critical usability questions for AWS Security:

How do I work this? 5 types of security policy and many attachment points interact within a complex control flow. 🤔

What can I do? The basic security policy language features are described on a single page, but engineers must understand volumes spread across specific AWS service docs. The AWS IAM user guide is over 800 pages long! 🤯

What happened? AWS provides no comprehensive way to understand the net effects of changes to principal and resource access. CloudTrail events provide delayed, sometimes incomplete feedback on why access was denied. 😕

Is this what I wanted? Difficult to tell if a given set of policies allows or denies access as intended. Critically, there is no comprehensive mechanism to identify excess access. 😖

AWS' flexibility requires engineers to gather and manage large amounts of security information in their heads. Norman calls this "knowledge in the head." AWS generally does not codify recommended security best practices directly in the service, which would be "knowledge in the world." Engineers must work hard to build this mental model and it takes time, so it will be different from colleagues' models.

In AWS' shared responsibility model, the responsibility for designing a cohesive set of access controls falls to the customer. AWS provides the security primitives, customers provide almost everything else.

AWS partially recognizes the burden of acquiring all this knowledge. They have tried to encode some security knowledge "in the world." Encoding knowledge in the world is "how designers can provide the critical information that allows people to know what to do, even when experiencing an unfamiliar device or situation." 2

Some examples of AWS encoding knowledge in the world are:

- Managed policies for particular jobs: Data Scientist, Power User, etc

- Control Tower and Landing Zones' Service Control Policies

- Config Rules

- Beanstalk

- "Level 2" and "Level 3" constructs in AWS CDK

But AWS is famously flexible, backwards compatible, and built by hundreds of independent teams. So it's unlikely we'll see a cohesive set of usable security tools and libraries emerge from AWS which are an ideal fit for your specific applications. It's even more unlikely those security tools would work in other Clouds which have similar problems.

Third parties can help. Internal platform teams, communities, and vendors can create opinionated, usable solutions that simplify security for their niche. As Norman says3:

Because behavior can be guided by the combination of internal and external knowledge and constraints, people can minimize the amount of material they must learn, as well as the completeness, precision, accuracy, or depth of the learning. They also can deliberately organize the environment to support behavior. This is how nonreaders can hide their inability, even in situations where their job requires reading skills.

Third-party toolmakers need to help AWS users create safer outcomes through a combination of approaches.

First, help users apply the knowledge they have to the unfamiliar AWS security system. Enable application engineers and others versed in the domain to describe what access should be.

Second, constrain configuration choices to a small set of safe options designed to work together.

Third, encapsulate expert knowledge into libraries and tools that meet engineers where they are and in the technology stack they already use.

These approaches have several benefits:

- Minimizes the AWS security knowledge the majority of engineers must learn to a manageable corpus.

- Improves communication with a higher level language, patterns, and reference architectures for designing and implementing safer systems.

- Enables engineers to deliver secure configurations everyday.

We must help engineers use the information they have to create great security outcomes.